As a teenager I felt a certain degree of pride in being a Klaus Schulze fan. His work was hard to find in record shops, and he didn’t get radio airplay (even on those European radio stations that were sometimes accessible on the shortwave band after dark), which meant that one often had to buy his LPs unheard. And the listening could be a challenge: tracks of 30 minutes duration, which meant narrower grooves on an LP, not ideal when pressed by Island UK who were notorious for using sub-standard cast-off vinyl from their classical releases.

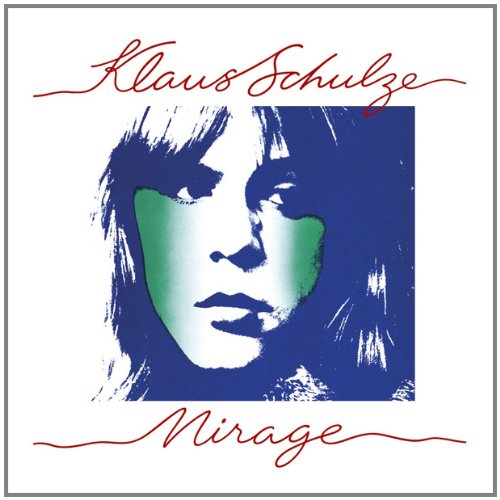

I’m pretty sure my first purchase was Mirage, and on first listening it seemed pretty opaque: 30 minutes of Moog-filtered noise on side 1, and a relentless sequenced pattern on side 2. I might have given up at that stage, but I came across a compilation LP called Brainwaves featuring various artists from the German Brain label, and this featured a short extract of a Schulze track called Stardancer: dynamic, melodic, percussive. That was enough to persuade me to give Schulze another go, and eventually I discovered the full-length version of Stardancer on the Body Love soundtrack. It’s one of many tracks which evidence Schulze’s skills as an improvisational keyboard soloist.

I think I had accidentally stumbled into Schulze’s creative peak, although many folk will argue that earlier works such as Blackdance and Timewind (or even Cyborg) should feature. For me, many repeated listenings to Mirage caused it to open and unfold into a truly deep, expansive and contemplative experience, and 40 years on I still find it incredibly immersive and rewarding. It is hard to overestimate its impact.

Of his other work of the period, the double album “X” is also strong and immersive, particularly the futuristic track Heinrich von Kleist, and the title track of the Dune album is a masterful piece of composition, with a beautiful reverberant but contained atmosphere. (Both Heinrich von Kleist and Dune heavily feature the Eventide harmoniser, which saw brief popularity in the late 1970s - see also Tangerine Dream’s Force Majeure.)

The shift from analogue to digital instruments and production in the mid 1980s affected Schulze strongly, and he seemed to shift away from immersive atmospherics and into sampled collage. He was incredibly prolific in the digital age, to a fault: some 40 albums plus numerous boxed set collections, editions and works. In my opinion, most are weak and even verge on unlistenable, but there are some gems, usually when Schulze veers back into the analogue domain: the “Dark Side of the Moog” collaborations with Pete Namlook are generally presentable and, in places, really good, as is much of the work with Lisa Gerrard. And to be fair, some of his “digital” albums such as Audentity and Trancefer are strong.

I have been long frustrated with this apparent emphasis on quantity rather than quality (telegraphed, in fact, by the sleeve notes in Mirage) but there’s enough superb work in his catalogue to make Klaus Schulze an incredibly important figure in electronic music, and a great loss.